I Introduction

There are few events that had a more profound impact on the way we visualise the inhabitants of Faërie, and especially the Elves, than the collaboration of the artist and illustrator Alan Lee and the film director Peter Jackson. Their joint vision of Tolkien’s Eldar as presented in the movie trilogies The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) and The Hobbit (2012-2014) has established the tall, slim, long-haired, fair-skinned, blue- or grey-eyed Eldar as the hegemonic version dominating the popular perception of Elves for the first two decades of the 21st century.

Illustration 1: Legolas (Orlando Bloom) in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings.

I have traced the process of how the imaginary of Faërie changed within the 20th and 21st centuries in another paper,[1] and would like to focus in this present essay on one aspect in particular: the reflection of the overall development from a folk-tradition based imaginary to an epic, high-fantasy influenced conceptualisation of the Elves. This can be done, incidentally, by looking at the work of Alan Lee during the period between the late 1970s and the turn of the millennium, which proved to be formative for the depiction of the Elves. Lee’s artistic development parallels and, in the end, influences the popular perception of Faërie and serves as a simplified mise en abyme that allows me to discuss these larger issues within the limits of a short paper.

II A (Very Short) Portrait of an Artist.

In the 21st century, information about public persons is no longer found primarily in the Who’s Who or the Dictionary of National Biography but in the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia where we also find, since 2004, a page dedicated to Alan Lee.[2]

Illustration 2: Alan Lee (2012).

Born in 1947, he had been working in the field of the fantastic for some time before he rose to international fame that came with the global success of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) movie trilogy. In the decades before the Jackson movies, Lee was known and loved by fantasy and folk-lore aficionados mainly for his numerous book- and cover-illustrations. Particularly his artwork for the 1992 centenary edition of The Lord of the Rings established him as a household name among Tolkien readers. Lee’s artistic media of choice have been and still are watercolour paintings and pencil sketches.[3]

Illustration 3: “Gandalf rides to Minas Tirith” by Alan Lee.

Especially his watercolours show inspiration from and similarities to, among others, Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)[4] whose work was known to and appreciated by Tolkien.

Illustration 4: “The Trees and the Axe” by Arthur Rackham (from Aesop’s Fables).

Lee, together with his slightly younger fellow artists John Howe (*1957)[5] and Ted Nasmith (*1956)[6], became one of the most prominent Tolkien illustrators and thus an obvious choice for film-director Peter Jackson, who was looking for concept artists for his The Lord of the Rings movies project. The rest, we could say, is (fantastic art) history.

III Fairies (1978)

In 1978, Alan Lee and Brian Froud[7] published a lavishly illustrated book with the title Fairies,[8] which, incidentally, provided the inspiration for the 25-minute animated television film Fairies (1981).[9]

Illustration 5: Fairies (1978) by Alan Lee and Brian Froud.

Illustration 6: Fairies (TV movie, 1981).

The book, more than the film, is of importance for our discussion of the development of the inhabitants of Faërie since it illustrates Lee’s broad range and catholic tastes in these matters. As the authors point out in their prefatory notes “A note on the use of the word FAERIE” and “A note on terminology”, the realm of Faërie contains many different fairie[10] species that are known under various names. Froud and Lee wisely accept the largely unregulated existence of a plethora of terms and concepts referring to the Otherworldly beings and thus keep company with Carl Linnaeus, whose systematic classification of the natural world stopped short of dragons, sirens, unicorns and the like.[11] Consequently, the pages of Fairies are populated with goblins, brownies, pixies, leprechauns, fairies, spriggans, redcaps, bogles, selkies, kelpies, elves, Sidhe etc.[12] and the authors take great pains to present as many of the variegated denizens of Faërie as possible. For many readers, including myself, Froud and Lee’s depictions and portraits of the Otherworldly sprites provided the first visualisation of concepts and names one may have read or heard, but that had as yet remained vague and beyond visual conceptualisation.

Illustration 7: “Fairie Rings” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 8: “Puck” by Brian Froud (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 9: “Jenny Greenteeth” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 10: “Phooka” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 11: “Brownie” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

What is also remarkable about Fairies is the synchronotopic co-existence of all the different types of faeries. Froud and Lee present a Faërie realm that is all-encompassing and that accommodates all the different and often very disparate Otherworldly beings.

Tolkien, too, started with a very mixed band of inhabitants of Faërie as, for example, the quote from the third chapter of The Book of Lost Tales 1 proves. The passage describing ‘The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor’ reads as follows:

About them [the Valar] fared a great host who are the sprites of trees and woods, of dale and forest and mountain-side, or those that sing amid the grass at morning and chant among the standing corn at eve. These are the Nermir and the Tavari, Nandini and Orossi, brownies, fays, pixies, leprawns, and what else are they not called, for their number is very great: yet must they not be confused with the Eldar, [i.e. the Elves …]. (Tolkien 1994: 66)

Unfortunately, Tolkien never painted this great host accompanying the Valar, but Froud and Lee’s illustrations for their Fairies-book could be used without problems to visualise these sprites.

Illustration 12: “Fairies” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Yet, their publication hosts within its covers, as we have seen, not only the smaller and bigger varieties of faeries (cf. Illustrations 13 & 14), but also the noble Tuatha de Danann and the Daoine Sidhe (cf. Illustrations 15 & 16).

Illustration 13: “Flower fairies” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 14: “Nuckelavee” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 15: “Daoine Sidhe” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 16: “Finvarra, King of the Daoine Sidhe” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

On the latter, the authors give the following perspicuous comment:

Following their defeat by the Milesians, those of the Tuatha de Danann who decided to stay in Ireland made their homes under the hollow hills or ‘Raths’ where they became the Daoine Sidhe. The Tuatha de Danann were originally gigantic but, in the course of time and with the encroachment of Christianity, as they diminished in importance, they correspondingly dwindled in size. (Fairies, n.p., page 36, position 50 in pdf version)

Illustration 17: “Hollow Hills” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

We have here an instance of the “dwindling” and “diminishing,” a process Tolkien described already in 1939 in his lecture-essay “On Fairy-stories” and which he linked to the development of fairy stories from nature myths[13]:

At one time it was a dominant view that all such matter was derived from “nature-myths.” The Olympians were personifications of the sun, of dawn, of night, and so on, and all the stories told about them were originally myths (allegories would have been a better word) of the greater elemental changes and processes of nature. Epic, heroic legend, saga, then localised these stories in real places and humanised them by attributing them to ancestral heroes, mightier than men and yet already men. And finally these legends, dwindling down, became folktales, Märchen, fairy-stories—nursery-tales. (Tolkien 2008: 42)

This “diminishing” can be seen as an explanation for the development of the Eldar of Old into the fairies of Shakespeare and Drayton.[14] Tolkien, in the appendix to The Lord of the Rings writes:

This old word [Elf/Elves] was indeed the only one available, and was once fitted to apply to such memories of this people as Men preserved, or to the makings of Men’s minds not wholly dissimilar. But it has been diminished, and to many it may now suggest fancies either pretty or silly, as unlike to the Quendi of old as are butterflies to the swift falcon—not that any of the Quendi ever possessed wings of the body, as unnatural to them as to Men. They were a race high and beautiful, the older Children of the world, and among them the Eldar were as kings, who now are gone: the People of the Great Journey, the People of the Stars. They were tall, fair of skin and grey-eyed, though their locks were dark, save in the golden house of Finarfin; and their voices had more melodies than any mortal voice that now is heard. (Tolkien 2004a: 1137, Appendix F)

Illustration 18: “Fingon’s decision” by Jenny Dolfen, showing a representative of the Eldar as Tolkien must have imagined them.

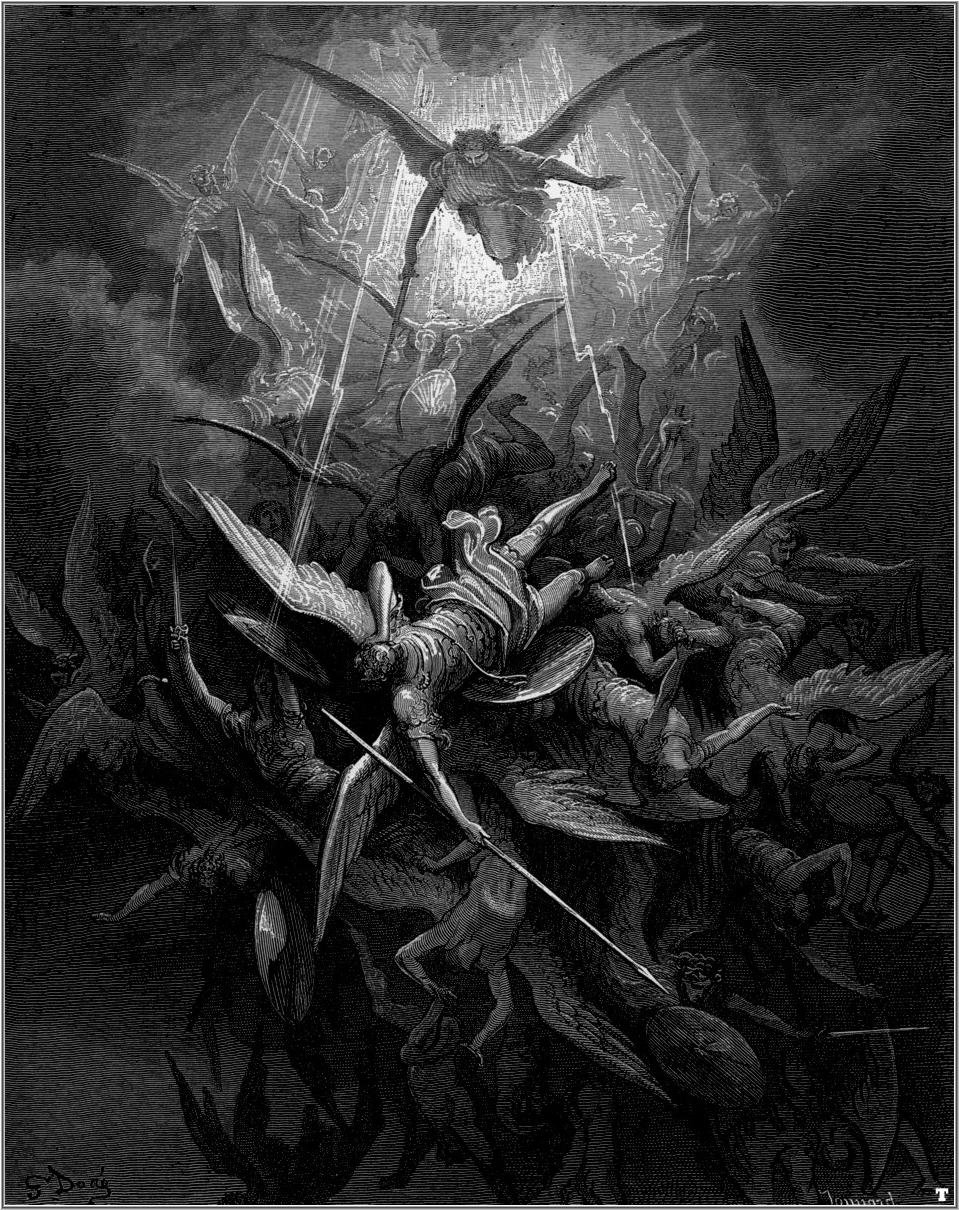

Thus, both Tolkien and the authors of Fairies share an aetiological narrative which implicitly provides an explanation for the existence of the seemingly incompatible traditions about the inhabitants of Faërie. According to this narrative, the impressive faeries of times past are the ancestors of the more recent diminutive sprites of folklore. Furthermore, the theory of diminishment is part of a more general attempt to accommodate the denizens of Faërie within the larger aetiological discourse explaining the creation of Heaven, Hell, and Earth. This tradition links the fairies/elves to the Luciferian rebellion in Heaven and argues that those angels who tried to remain neutral in the conflict between God and Lucifer were then exiled onto earth where they lost some of their originally angelic status and became the fairies (cf. Sugg 2018: 20-30).[15]

Illustration 19: “The Fall of the Angels” by Gustave Doré (for John Milton’s Paradise Lost [1866]).

This process, which may be imagined as gradual and happening to different inhabitants of Faërie at different speed, would provide an explanation for the variegated nature of the fairie queens and kings’ followings, as encountered, for example, in Arthur Rackham’s illustration of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Illustration 20: “The Meeting of Oberon and Titania” (1908) by Arthur Rackham.

Yet Fairies is not only important for providing an explanatory framework for the great variety and diversity found among the inhabitants of Faërie but even more crucial for the establishment of a visual imaginary that gives expression to these variegated terms and concepts. Some of the less aesthetically pleasing creatures can trace back their ancestry via the medieval depictions of demons (cf. Illustration 25) to the ancient cultures of the Near East and, in Lee’s artistic interpretation, become the ancestors of Tolkien’s orcs and hobgoblins.

Illustration 21: “Orcs” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

Illustration 22: “Redcap” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 23: “Fairies on the Eastern Green” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 24: “The Unseelie Court” by Alan Lee (from Fairies [1978]).

Illustration 25: “The Temptation of St. Anthony” by Martin Schongauer (ca. 1480-90).

Lee’s recourse to some of the inhabitants of Faërie as inspirations for his depiction of Tolkien’s orcs thus follows the Professor’s own speculations about a common origin of Elves and Orcs, which could be seen as Tolkien’s very own version of “the Fall of the Angels”:

But of those unhappy ones who were ensnared by Melkor little is known of a certainty. For who of the living has descended into the pits of Utumno, or has explored the darkness of the counsels of Melkor? Yet this is held true by the wise of Eressëa, that all those of the Quendi who came into the hands of Melkor, ere Utumno was broken, were put there in prison, and by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus did Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes. For the Orcs had life and multiplied after the manner of the Children of Ilúvatar; and naught that had life of its own, nor the semblance of life, could ever Melkor make since his rebellion in the Ainulindalë before the Beginning: so say the wise. And deep in their dark hearts the Orcs loathed the Master whom they served in fear, the maker only of their misery. This it may be was the vilest deed of Melkor, and the most hateful to Ilúvatar. (Tolkien 1977: 50)

This leaves the illustrations of the human-sized (or taller) Daoine Sidhe as the logical choice for Tolkien’s Elves. And indeed, the illustrations Lee created for the Gwyn and Thomas Jones’s edition of The Mabinogion (1982) helped him to develop this aspect further.

IV The Mabinogion (1982)

The Mabinogion[16] is a collection of Celtic myths, legends, and proto-romances which have survived to the greater part in two late 14th-century manuscripts.

Illustration 26: Cover of the Mabinogion (cover-art by Alan Lee [1982]).

Although the title was already used in 1795 for William Owen Pughe’s translation of Pwyll,[17] it becomes widely known only with Lady Charlotte Guest’s bilingual (Welsh and English) edition (1838-1845). In The Mabinogion, (semi-)historical persons rub shoulders with mythological beings; and some denizens of the Otherworld, such as Rhiannon, are in close contact with the heroes of our world.

Illustration 27: “Rhiannon riding in Arbeth’”(from The Mabinogion (1877), translated by Charlotte Guest).

Illustration 28: “Rhiannon” by Alan Lee (from The Mabinogion [1982]).

Most importantly, they are, by their appearance alone, hardly distinguishable from normal human beings and can pass as companions or spouses. This links them to similarly otherworldly characters in, for example, Marie de France’s Lays,[18] where we also find fairy knights engendering offspring onto (more or less willing) human ladies. These two collections of tales must be put next to the early 14th-century Middle English poem Sir Orfeo, which was known to Tolkien at the latest from his compilation of A Middle English Vocabulary (1922), a supplement for Sisam’s anthology of Fourteenth Century Verse and Prose (1921).[19] Sir Orfeo features elves that are at once courtly, noble, and threatening: the king of Faërie abducts Orfeo’s wife Heurodis and keeps her at his court, which is a strange synthesis of Celtic (sidhe) and classical mythological (Hades, Orpheus) elements that are presented within a medieval-courtly framework. The Otherworld at large is similar to our own world and the King of Faërie and his retinue own castles, go hunting in woods and ride through lush pastures.[20]

The vital and for our purpose relevant characteristic of all three textual witnesses is their connection with and contribution to the imaginary of the Celtic Otherworld and its inhabitants. Thus, both Tolkien and Lee would have been exposed during a crucial phase of their artistic development[21] to the concept of the noble, awe-inspiring but also somewhat threatening elves.[22]

This also meant that the visual realisations of the Celtic imaginary as found in the illustrations of Lady Charlotte Guest’s The Mabinogion or the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers would provide inspiration for how to depict the denizens of the Otherworld. A painting such as The Riders of the Sidhe (1911) by John Duncan (1866-1945), a leading representative of the Celtic revival, captures the spirit of the Celtic imaginary.

Illustration 29: The Riders of the Sidhe (1911) by John Duncan.

The connection to the Celtic sidhe is also important for the depiction of the Wood-elves, and especially of the royal underground palace in The Hobbit. The term sidhe originally denotes the earthen mounds which are, according to Irish folklore and mythology, the homes of the aos sí,[23] the People of the Mounds, who are often associated with or identified as elves and fairies. Tolkien himself strengthened the sidhe connection not only through his description of the royal underground palace, but also by means of his drawing “The Elvenking’s Gate”[24] as an illustration for the first edition of The Hobbit.

Illustration 30: “The Elvenking’s Gate’”(1937) by J.R.R. Tolkien.

The black-and-white picture, drawn for the first edition of The Hobbit (1937), shows a tree-lined pathway running straight up to a monolithic entrance to a hill on the other side of a river. This sidhe connection is important for the visualization of the Elves since it links them to the Celtic myths and legends, which had become widely popular thanks to Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation of The Mabinogion (1838-1845). Alan Lee’s congenial illustrations to the 1982 edition of The Mabinogion bring the lords and ladies of Faërie to life and he prepares, maybe not quite unwittingly, the way for the hegemonic elf of the 21st century.

Illustration 31: “The Lady of the Fountain” by Alan Lee (from The Mabinogion [1982]).

V The Lord of the Rings Centenary Edition (1992)[25]

The prominence of female representatives of Faërie in Lee’s illustrations to The Mabinogion is mainly due to the fact that the human male protagonists of the tales come into contact with predominantly female denizens of the Otherworld, which gives them a narrative eminence that is not necessarily in accordance with the population statistics of Faërie. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings also features a “Lady of the Fountain” in form of Galadriel and Lee depicts her in his illustration to the chapter “The Mirror of Galadriel” accordingly as a typical “Weisse Frau”[26] of the Germanic tradition who, in turn, is an incarnation of the White Goddess archetype.[27]

Illustration 32: “The Mirror of Galadriel” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

Illustration 33: Cover of The White Goddess (1948) by Robert Graves.

Illustration 34: Statue of the goddess Cybele (ca. 50 AD), a representative of the White Goddess archetype.

As a consequence, Galadriel may be seen as the primary embodiment of female Elvendom, yet she is at least as much the living archetype of the White Goddess and, as such, transcends her role as female Elf. This has consequences for the internal economy of the later movie adaptations, which aim at counterbalancing this by filling the gap in the matrix for the “average female Elf” by bolstering the role of existing female Elves, such as Arwen, or even inventing less exalted ones, such as Tauriel. My primary concern in this paper is, however, with the search for the paradigmatic Elf in the 1992 centenary edition of The Lord of the Rings. The result was, on the one hand, somewhat disappointing but, on the other, in tune with Tolkien’s handling of the Elves. They are there in Lee’s atmospheric illustrations yet not so much centre stage but blending into the surroundings and therefore often almost invisible to the casual observer. This is also true for the few instances where we have Elves in Lee’s illustrations of the 1997 edition of The Hobbit. Thus, we can distinguish some Elves swimming in the Loudwater or resting on the banks of the river.

Illustration 35: “Approach to Rivendell” by Alan Lee (from The Hobbit [1997]).

In the 1992 edition of The Lord of the Rings Elves feature prominently for the first time in the watercolour depicting the hobbits’ meeting with Gildor Inglorion and his companions in the Shire.

Illustration 36: “Meeting with Gildor Inglorion” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

There we get a good and unobstructed look at (presumably) Gildor and some of his fellow Elves, both male and female. They all wear flat shoes (not boots!), leggings-type trousers, and tight-fitting, long-armed tunics over which they don a cloak. They are all beardless and have long fair hair that falls in strands (maybe even small braids?) over their shoulders. Lee also makes a point of showing clearly two of their ears: they are not pointed (nor are those of the hobbits)![28] Later paintings for the volume show mostly Legolas, who fits the mould established by Gildor and his companions. Thus, we first encounter Thranduil’s son in the illustration depicting the Council of Elrond.

Illustration 37: “The Council of Elrond” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

There we see a beardless, slim Elf with light brown hair facing a seated, bearded Elrond who seems of heavier build. This impression is further supported by the picture showing the Fellowship in front of the Doors of Moria.

Illustration 38: “The Doors of Moria” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

Legolas is standing next to Boromir, and he is somewhat shorter than the Gondorian, which is in accordance with Tolkien’s text.

The impression of a lithe, athletic Elf-warrior is further strengthened by Lee’s illustrations of “The Three Hunters,” where we see Legolas depicted from behind, and “The Passing of the Grey Company,” where we see Legolas and Gimli on horseback in the background.

Illustration 39: “The Three Hunters” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

Illustration 40: “The Passing of the Grey Company” by Alan Lee (from The Lord of the Rings [1992]).

Thus, the stage is set for Peter Jackson’s entrance.

VI Peter Jackson’s Movie Trilogies (2001-2003 & 2012-2014)

Jackson’s successful enlistment of Alan Lee, together with John Howe, as chief conceptual designers for his The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit movie trilogies meant that Lee’s slightly blurred vision of the denizens of Faërie would become the hegemonic depiction of Elves for the next two decades. Yet while his water-colour paintings lent themselves ideally as blueprints for the otherworldly realms of Faërie, such as Lothlórien, it could not be avoided to eventually show some of the Elves in HD. In The Lord of the Rings movie trilogy, Legolas (Orlando Bloom), as the Elvish representative in the Fellowship, thus became “the face of Elvendom.”

Illustration 41: Legolas (Orlando Bloom) in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings.

Jackson’s takeover of the production of The Hobbit movie project guaranteed an artistic continuity without radical breaks and deviations from the earlier vision of the Elves. Innovations were introduced only carefully and following the logic of the blockbuster cinema. Thus, Jackson gives us the newly created character of the red-haired she-Elf Tauriel as a counterpart and potential love-interest to the action-Elf Legolas.

Illustration 42: Tauriel (Evangeline Lilly) in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit.

Also, Jackson puts the depiction of Legolas’s father back on track, so to speak. Earlier movies, such as the animated The Hobbit (Rankin & Bass 1977), had presented Wood-elves that were more akin to goblins.

Illustration 43: Wood-elves in Rankin & Bass’s The Hobbit.

Illustration 44: The King of the Wood-elves in Rankin & Bass’s The Hobbit.

This was remedied in Jackson’s The Hobbit (2012-2014) in which the American actor Lee Pace gives us an iconic Thranduil. Lee Pace, with his 1,96 metres, not only looks the part, echoing the haughty nobility of Horus Engels’s illustration, but he also succeeds in imbuing his character with an uncanny Otherworldly cruelty that is reminiscent of the Elvenking in Sir Orfeo.

Illustration 45: Thranduil (Lee Pace) in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit.

Illustration 46: The King of the Wood-elves (1957) by Horus Engels.

VII Beyond the Albus Jacsonensis

Alan Lee’s Elves in the interpretatio Jacsonensis have become so successful because they take up some older elements, refining and adapting them to fill a gap in the visual tradition. As a consequence, they become the hegemonic model for how to envisage the non-diminutive inhabitants of Faërie and provide the starting point from which further developments take place. While Jackson’s The Hobbit (2012-2014) movie trilogy, on the one hand, reinforced the hegemonic picture of the blonde, blue- or grey-eyed, fair-skinned, slim, martially skilled Elf, it also, on the other hand, opened the door for variations of this basic pattern, most prominently in the form of the red-haired female Wood-elf Tauriel. Jackson had already tried to counterbalance the numeral predominance of male protagonists in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings by upgrading Arwen in his first movie trilogy. However, Arwen, as the daughter of Elrond Half-elven and the granddaughter of Galadriel, has never been intended as representative of the “average Elf”—she has always been too much in a category of her own. The introduction of a newly invented female Elf character was thus merely a logical step towards a greater gender parity. And to make her a redhead earned Jackson some more brownie points on the inclusion scale. This trajectory has been followed and developed by video-games and fantasy artists, so that the Amazon Prime series The Rings of Power (2022- ) features Elves and other protagonists with an obviously non-white Caucasian background, most prominently the Elf Arondir (played by Ismael Cruz Córdova).

Illustration 47: The Elves of The Rings of Power (1st Season).

Additionally, we see a differentiation by means of hairstyles. The long-haired Elf-lords such as Gil-galad (Mark Ferguson) or the she-Elves such as Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) are contrasted with short-haired Elves, such as military-style Arondir or the 1950s blow-dry style Elrond (Robert Aramayo) and Celebrimbor (Charles Edwards). We have not seen an Elf with a beard or a moustache yet, but since Círdan the Shipwright sports a beard,[29] I am preparing myself mentally to possibly encounter a hipster-style Elf in the next season of The Rings of Power.

Illustration 48: Círdan the Shipwright.

Depending on one’s point of view, these new variations and deviations from the hegemonic Albus Jacsonensis have been either heavily criticised as a woke aberration or welcomed as part of the adaptation of Tolkien’s legendarium for a 21st-century audience.[30] Tolkien himself did not visualise any of his Elves with an African or Oriental ethnical background—primarily because he based his legendarium largely on the cultural heritage of north-western Europe.[31] Yet this does not exclude variation.[32] As we have seen, Círdan breaks the mould of the beardless Elf, and we have enigmatic figures such as Eöl the Dark Elf,[33] whose name is suggestive, though, it is unlikely that Tolkien did envisage him as an “Elf of Colour.”

VIII Conclusion

The story of the visualisation of the elves in the 20th and 21st centuries is, as I have shown in the preceding pages, intimately linked with the development of Tolkien’s legendarium and the role of the Eldar. While Tolkien’s earliest known poems like “Wood-sunshine” (1910) still feature woodland sprites that are indebted to the Victorian tradition, we soon notice that Tolkien, with the rise of the Eldar, reaches back to an alternative tradition of the human-sized denizens of Faërie. Echoes of the co-existence of the two concepts are still to be found in e.g. Tolkien’s description of the Elves of Rivendell in the children’s tale The Hobbit (1937), yet he was aware that he had to differentiate between the various categories of (super-)natural beings and, eventually, to get rid of the flower fairy element. As early as The Book of Lost Tales 1, he pointed out that the numerous sprites populating the British countryside must “not be confused with the Eldar” (Tolkien 1994: 66). Indeed, it can be argued that the modern differentiation between the human-sized Elves and the lesser sprites of the countryside is due to the popularity of Tolkien’s work and, via Peter Jackson’s movies, the impact of Alan Lee’s vision of Tolkien’s Elves. Without the success of The Lord of the Rings both as a text and as a movie trilogy, the image of the Elf might be still indebted to the flower fairy tradition. Other authors would and actually did come up with concepts of Elves that differ radically from the Victorian tradition and are closer to Tolkien’s Eldar, such as the elves in Poul Anderson’s novel The Broken Sword, which was published on 5 November 1954, just three months after The Fellowship of the Ring (29 July 1954).

Illustration 49: Cover of Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword (1954).

Yet despite the critical acclaim for Anderson’s novel, it was never able to rival the popular success of Tolkien’s epic and consequently Anderson’s depiction of the elves never gained sufficient traction to challenge the noble Eldar of Middle-earth. Considering the depiction of the elvish protagonist on the cover of the 1971 edition, that might have been a good thing.

Illustration 50: Cover of Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword (1971 edition).

Looking back at the development of the Elves from flower fairy to the Albus Jacsonensis and beyond, I sometimes wonder what would have happened if Tolkien had never published his epic tale or Peter Jackson had never asked Alan Lee to join him as chief conceptual designer. But as it is, chance favoured their conception of the denizens of Faërie, “if chance you call it” (Tolkien 2004a: 126)—and that is fine with me.

[1] See Honegger ‘Beautiful and sublime’ (forthcoming).

[2] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Lee_(illustrator)>. See also the somewhat dated site <https://alan-lee.narod.ru/Bio.htm>.

[3] A good selection of his work can be found at <https://www.iamag.co/the-art-of-alan-lee/>.

[4] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Rackham>, where you can find also a representative selection of his artwork.

[5] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Howe_(illustrator)>.

[6] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ted_Nasmith>.

[7] On Brian Fround, see <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Froud>.

[8] Brian Froud and Alan Lee. 1978. Fairies. Edited and designed by David Larkin. London: Souvenir Press.

[9] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faeries_(1981_film)>.

[10] The authors, in their prefatory note, make the distinction between faerie, pl. faeries as denoting the inhabitants of Faërie in general, and fairy, pl. fairies as denoting “a particular, diminutive, generally female species of Faerie.”

[11] See Honegger (2019: 17-20) on Linnaeus’s treatment of the dragon within his systematic classification.

[12] Fairies also reads a bit like an illustration and visualization of such enigmatic lists as the one found in the second volume of The Denham Tracts (Denham 1895: 77-80), where we also find, on page 79, ‘hobbits’.

[13] See, for example, Tolkien (2008: 43, 91 (Mab or Medb was Queen of Connacht in the heroic Ulster cycle of Irish myth, which tradition assigns to the beginning of the Christian era. Over time her status dwindled from heroic myth to fairy tale, and her stature dwindled as well.), 223, 227).

[14] See William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595) and Michael Drayton’s Nymphidia or The Court of Faery (1627), where we have diminutive, mostly harmless creatures who have little in common with the demonic “ylfe” of the Old English epic Beowulf (ca. 800 AD) or the threatening inhabitants of the Otherworld in the Middle English romance Sir Orfeo (ca. 1330).

[15] Eventually occurring similarities of the Elves to the angels as represented in the iconography of the Catholic church are therefore not completely unfounded.

[16] Tolkien knew The Mabinogion in translation and the original. See Cilli (2019: 110, entries 894-899) and Cilli (2023, entries 876-881) for the evidence we have from Tolkien’s references to The Mabinogion. Tolkien inscribed his Everyman edition of Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation with “1 May 1913” (Scull & Hammond 2017: 48).

[17] The full title reads: ‘The Mabinogion, or Juvenile Amusements, being Ancient Welsh Romances’.

[18] The lays are in French, but were written in England during the second half of the 12th century. Tolkien owned by ca. 1920 two of the standard editions (cf. Cilli 2019: 283-184, items 1515-1516).

[19] See Tolkien (2004b) and also Honegger (2010).

[20] For a description of these aspects of Faërie, see especially lines 141-161 in Tolkien’s translation of the poem (Tolkien 1995: 126).

[21] See Fimi (2008: 9-61) for a discussion of Tolkien’s development.

[22] The alfr of the Scandinavian tradition are a separate problem and are not taken into consideration in this paper. For a competent discussion, see Shippey (2005).

[23] The older form of aos sí is aes sídhe, and thus sídhe is often used to refer to both the mounds and their inhabitants.

[24] See <https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/User:Aule_the_Smith/The_Elvenking%27s_Gate>.

[25] “Centenary” here refers to Tolkien’s 100th birthday. He was born 3 January 1892.

[26] See Grimm (1875-78, II, 803-809).

[27] See Graves’s classical study The White Goddess (first edition 1948; expanded edition 1966).

[28] The ears of Lee’s goblins and orcs, however, are clearly pointed.

[29] “As they came to the gates Círdan the Shipwright came forth to greet them. Very tall he was, and his beard was long, and he was grey and old, save that his eyes were keen as stars; and he looked at them and bowed, and said: ‘All is now ready.’” (Tolkien 2004a: 1030).

[30] See Stuart (2022) for an excellent study of race and racism in Tolkien’s works.

[31] See Honegger (forthcoming, ‘From Old English orcneas to George MacDonald’s Goblins with Soft Feet)’ on the possible Oriental origin of the ‘little people’ (aka fairies) in the context of the Turanian-origin theory.

[32] See Shippey (2005).

[33] He features in chapter 16 “Of Maeglin” of the “Quenta Silmarillion” (Tolkien 1977: 131-139). The epithet “Dark Elf” seems to refer to his choice of dwelling place in the darkest place of the forest of Nan Emloth and his predilection for the night and the stars rather than the sunlight and is not likely to suggest an “ethnic” background since he is “of the kin of Thingol” (Tolkien 1977: 132).

Bibliography: References and Further Reading

Bakshi, Ralph (dir.). 1978. The Lord of the Rings. USA.

Beddoe, Stella. 1997. “Fairy Writing and Writers.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 23-31.

Bown, Nicola. 2001. Fairies in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carpenter, Humphrey. 1995. J.R.R. Tolkien. A Biography. First edition 1977. Paperback edition. London: HarperCollins.

Cilli, Oronzo. 2019. Tolkien’s Library: An Annotated Checklist. Edinburgh: Luna Press.

Cilli, Oronzo. 2023. Tolkien’s Library: An Annotated Checklist. Second revised and expanded edition. Edinburgh: Luna Press. [epub]

Denham, Michael Aislabie. 1895. The Denham Tracts. A Collection of Folklore by Michael Aislabie Denham. Reprinted from the original tracts and pamphlets printed by Mr. Denham between 1846 and 1859. Volume 2. Edited by Dr. James Hardy. Published for the Folklore Society. London: David Nutt. <https://archive.org/details/denhamtractscoll00denh/mode/2up>

Ferré, Vincent and Frédéric Manfrin (eds.). 2019. Tolkien. Voyage en Terre du Milieu. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France /Christian Bourgois editeur.

Fimi, Dimitra. 2008. Tolkien, Race and Cultural History. From Fairies to Hobbits. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Froud, Brian and Alan Lee. 1978. Fairies. Edited and designed by David Larkin. London: Souvenir Press.

Geoffrey of Vinsauf. ca. 1210. Poetria Nova. Translated by Margaret F. Nims. 1967. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Gere, Charlotte. 1997. “In Fairyland.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 63-72.

Graves, Robert. 1966. The White Goddess. A Historical Grammar of Poetric Myth. Amended and enlarged edition. First edition 1948. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Grimm, Jakob. 1875-78. Deutsche Mythologie. Three volumes. Fourth edition. First edition 1835. Reprint 1992. Wiesbaden: Drei Lilien Verlag.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. 1995. J.R.R. Tolkien. Artist & Illustrator. London: HarperCollins.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. 2011. The Art of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien. London: HarperCollins.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. 2015. The Art of The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. London: HarperCollins.

Hillman, Thomas. 2018. “These are Not the Elves You’re Looking For: Sir Orfeo, The Hobbit, and the Reimagining of the Elves.” Tolkien Studies 18: 33-58.

Honegger, Thomas. 2010. “Fantasy, Escape, Recovery, and Consolation in Sir Orfeo: The Medieval Foundations of Tolkienian Fantasy.” Tolkien Studies 7: 117-136.

Honegger, Thomas. 2019. Introducing the Medieval Dragon. Medieval Animals Series Volume 1. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Honegger, Thomas. forthcoming. “From Old English orcneas to George MacDonald’s Goblins with Soft Feet: Sources of Inspiration and Models for Tolkien’s Orcs from English Literature.” In Delila Jordan and Kerstin Droß-Krüpe (eds.). Eine kleine Geschichte der Orks. Der monströse Feind im Wandel der Zeit. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Honegger, Thomas. forthcoming. “Beautiful and sublime – and never mind the pointed ears. Visualizing the Elves throughout the centuries.” Myth and Middle Ages. Paradigms of Pictorial Fantasy Aesthetics (1880-2020). Reihe Populäres Mittelalter. Bielefeld: transcript.

Jackson, Peter (dir.). 2001-2003. The Lord of the Rings. New Zealand.

Jackson, Peter (dir.). 2012-2014. The Hobbit. New Zealand.

Jackson, Russell. 1997. “Shakespeare’s Fairies in Victorian Criticism and Performance.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 39-45.

Jones, Gwyn and Thomas Jones. 1982. Mabinogion. Illustrated by Alan Lee. Hendrik-Ido-Ambacht: Dragon’s Dream.

Kowalik, Barbara. 2013. “Elbereth the Star-Queen Seen in the Light of Medieval Marian Devotion.” In Barbara Kowalik (ed.). 2013. O What a Tangled Web. Tolkien and Medieval Literature. A View from Poland. Cormarë Series 29. Zurich and Jena: Walking Tree Publishers, 93-113.

Kowalski, Jesse (ed.). 2020. Enchanted. A History of Fantasy Illustration. Norman Rockwell Museum. New York and London: Abbeville Press Publishers.

Lambourne, Lionel. 1997. “Fairies and the Stage.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 47-53.

Maas, Jeremy. 1997. “Victorian Fairy Painting.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 11-21.

MacLeod, Jeffrey J. and Anna Smol. 2017 “Visualizing the Word: Tolkien as Artist and Writer.” Tolkien Studies 14: 115-131.

Martineau, Jane (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton.

Matthew of Vendôme. ca. 1175. Ars versificatoria. (The Art of the Versemaker). Translated by Roger P. Parr. Milwaukee WI: Marquette University Press, 1981.

McIlwaine, Catherine (ed.). 2018. Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth. Oxford: Bodleian Library.

McIlwaine, Catherine (ed.). 2018. Tolkien Treasures. Oxford: Bodleian Library.

Purkiss, Diane. 2007. Fairies and Fairy Stories. A History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing.

Rankin, Arthur Jr. and Jules Bass (dir.). 1977. The Hobbit. USA.

Ryan, John S. 2009. “Before Puck – the Púkel-men and the puca.” In John S. Ryan. 2009. Tolkien’s View. Windows into his World. Cormarë Series 19. Zurich and Jena: Walking Tree Publishers, 223-233.

Schindler, Richard Allen. 1988. The Art to Enchant: A Critical Study of Early Victorian Fairy Painting and Illustration. Dissertation Brown University.

Scull, Christina and Wayne G. Hammond. 2017. The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Volume 1: Chronology. Volumes 2&3: Reader’s Guide. First edition 2006. Revised and expanded edition. Boston, MA and New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Shippey, Tom A. 2005. “Alias Oves Habeo: The Elves as a Category Problem.” In Tom Shippey (ed.). 2005. The Shadow-Walkers: Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous. (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 291). Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies/Turnhout: Brepols, 157-187.

Silver, Carole G. 1999. Strange & Secret Peoples. Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stuart, Robert. 2022. Tolkien, Race, and Racism in Middle-earth. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sugg, Richard. 2018. Fairies. A Dangerous History. London: Reaktion Books. [epub]

Tankard, Paul. 2017. “‘Akin to my own Inspiration’: Mary Fairburn and the Art of Middle-earth.” Tolkien Studies 14: 133-154.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1977. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1979. Pictures by JRR Tolkien. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1984. The Hobbit. Illustrated by Michael Hague. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1992a. The Book of Lost Tales 2. (The History of Middle-earth 2.) Edited by Christopher Tolkien. First edition 1984. Paperback edition. London: Grafton.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1992b. The Lord of the Rings. Three volume set. Illustrated by Alan Lee. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1994. The Book of Lost Tales 1. (The History of Middle-earth 1.) Edited by Christopher Tolkien. First edition 1983. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. (trans.). 1995. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. First edition 1975. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1997. The Hobbit. Illustrated by Alan Lee. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1998. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. Illustrated by Ted Nasmith. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 1999. The Hobbit. A 3-D Pop-Up Adventure. Illustrated by John Howe. London: HarperFestival.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2000. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien. First edition 1981. Reprint. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2002. The Annotated Hobbit. Edited and annotated by Douglas A. Anderson. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2004a. The Lord of the Rings. 50th Anniversary One-Volume Edition. Boston MA and New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2004b. “Sir Orfeo: A Middle English Version by J.R.R. Tolkien.” Edited by Carl F. Hostetter. Tolkien Studies 1: 85-123.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2008. Tolkien On Fairy-stories. (Expanded edition, with commentary and notes; first edition 1947). Edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson. London: HarperCollins.

Trimpe, Pamela White. 1997. “Victorian Fairy Book Illustration.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 55-61.

Warrack, John. 1997. “Fairy Music.” In Jane Martineau (ed.). 1997. Victorian Fairy Painting. Royal Academy of Arts. London: Merrell Holberton, 33-37.

Wenzel, David. 2006. J.R.R. Tolkien: The Hobbit. Graphic novel. Revised edition. First edition 1990. London: HarperCollins.